This article explores the benefits of marine biology internships and features examples of GVI's marine conservation programs. Learn more!

Petrina Darrah

Posted: May 15, 2025

Clare Woolston

Posted: March 17, 2021

True or false: sicklefin lemon sharks rigorously and persistently defend themselves when provoked?

Together, we’ll deep dive into the world of this vulnerable species. While submerged, we’ll learn interesting facts about them and their habitats too.

Sicklefin lemon sharks are known to be cautious when approached and will often retreat. However, as with any wild animal, they can be dangerous when provoked.

They have a reputation for defending themselves persistently and vigorously when they feel they’re being attacked, for example, if they’re touched, poked or speared by divers or spearfishers. But, they’re usually very shy.

Sicklefin lemon sharks are found in Australia, Fiji, Madagascar, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Seychelles and Vanuatu.

Historically, they were found in India and Thailand. Now they are locally extinct in those places, because they were overharvested. They used to be recorded frequently in Indonesia, but that’s no longer the case.

Original photo: Julien Bidet

In 2003, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) assessed the global population of sicklefin lemon sharks, and listed it as decreasing. The global population is classified as vulnerable on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

After all these years since this assessment, known threats to these sharks have been increasing, meaning they could be more at risk now. And, the IUCN has since identified the need to update the global assessment.

The sicklefin lemon shark is also an understudied species, which hampers conservation efforts. To know how to best conserve a species, you need to know why numbers are decreasing. Is it due to habitat loss? Do they take a long time to reach sexual maturity? Or, are they overharvested, for example?

Scientific data from projects like our sicklefin lemon shark and turtle conservation project are critical when this species is assessed by the IUCN again. It’ll help answer these types of questions, so the next assessment is better informed.

The reason for the decrease in sicklefin lemon shark population numbers is multifaceted, from the threats they face to the species’ reproductive traits.

Sicklefin lemon sharks are “homebodies”. A landmark study done in 1984 in Seychelles, showed adult sicklefin lemon sharks roam about 1,3 kilometres from their habitats. This is different from great white sharks, for example, that undertake transoceanic migrations.

Home for adult sicklefin lemon sharks is coral reefs, and the waterlogged, sandy plateaus nearby. Newborns, known as pups, and juveniles are found in coral atoll lagoons, and in mangrove estuaries.

Their small, coastal habitat range and limited movements mean sicklefin lemon sharks are susceptible to overharvesting at a local level.

Original photo: MissMegido

Sicklefin lemon sharks have a low reproductive capacity. Their gestation period is ten to 11 months and they have between one and 12 pups per litter. They also have slow growth rates and only reach sexual maturity when they’re around 2,2 metres long.

In the areas surrounding Curieuse island, they grow just 5,4 centimetres per year. We know this from the data our wildlife conservation participants have collected in partnership with Seychelles National Parks Authority staff.

Take this growth rate and their required size for sexual maturity into consideration. Since pups measure 60 centimetres when born, it could take up to 29 years before sicklefin lemon sharks are ready to breed. However, this needs to be confirmed via further research.

So, what does all of this mean? Well, basically, once sicklefin lemon shark populations have been depleted, they’ll have limited capacity to recover.

Coral reefs are one of the places that sicklefin lemon sharks call home. The IUCN ranks coral reefs as one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world. Between 2014 and 2017, we saw mass bleaching events affecting the world’s coral reefs. When this happens, the coral often dies, meaning this habitat type is lost.

This was the result of increased global surface temperatures due to climate change. Over one-third of the world’s coral reef species are now threatened with extinction.

Sicklefin lemon sharks’ other key habitat, mangrove forests, are also one of the fastest disappearing habitats worldwide (with 0,3–0,6% being lost per year). Globally, 20–35% of mangrove area has been lost since approximately 1980. This is due to a combination of coastal development, climate change, agricultural development and logging.

GVI is running marine conservation programs around the globe, some of which focus on coral reef research and mangrove monitoring.

To effectively conserve and manage a species, we need to know more than where they live. We need to understand how a species uses the different habitats in which it’s found, throughout its various life stages.

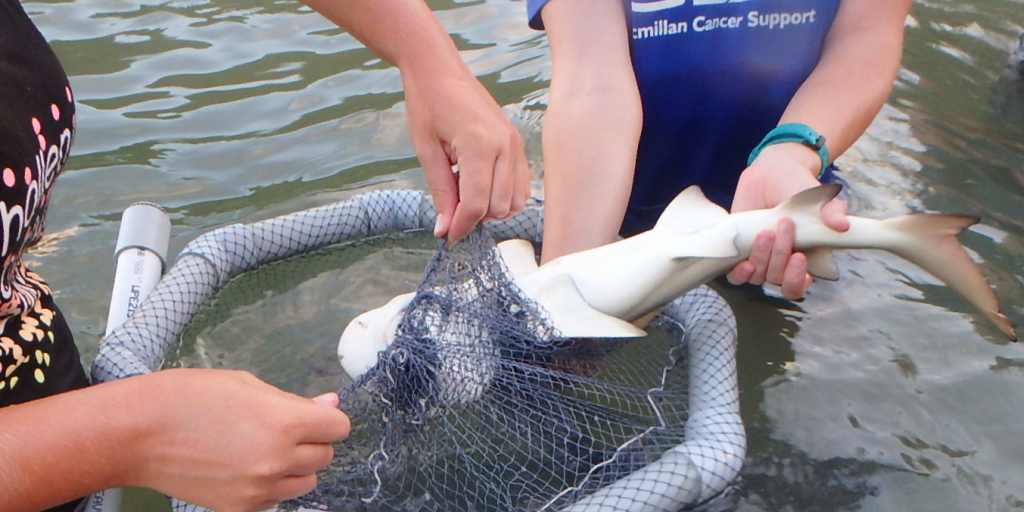

GVI’s participants investigate how juvenile sicklefin lemon sharks make use of their habitat in our project on Curieuse island. Participants humanely catch juveniles and once caught, they’re fitted with acoustic transmitters. They’re then released back into the water, and their movement patterns are tracked using a hydrophone.

Gathering this data will help make a lasting impact for sicklefin lemon sharks by contributing to the body of scientific knowledge about them.

Government agencies like our partner, the Seychelles Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change, use the scientific data we collect as well as data from other reputable sources. This is so they can make well-informed decisions, like creating fishing strategies that don’t cause over-harvesting.

Our participants also plant mangrove seedlings on Curieuse island and other Seychelles locations. This is to contribute to the restoration of degraded mangrove forests in partnership with the Terrestrial Restoration Action Society of Seychelles.

When you’re not participating in our sicklefin lemon shark and turtle conservation project, you can still make a meaningful impact on the well-being of sicklefin lemon sharks. When you travel, make proactive, informed choices that add to the well-being of marine ecosystems. Avoid shark-fin soup and purchasing shark-tooth souvenirs.

You can also donate funds to GVI Charitable Programs that invests in our on-the-ground activities that build on the conservation of the sicklefin lemon shark, as well as hawksbill turtles and Aldabra giant tortoises.

Take a look at our sicklefin lemon shark conservation program in Seychelles and see how you can learn more facts about these creatures first-hand.

This article explores the benefits of marine biology internships and features examples of GVI's marine conservation programs. Learn more!

Petrina Darrah

Posted: May 15, 2025